The Film:

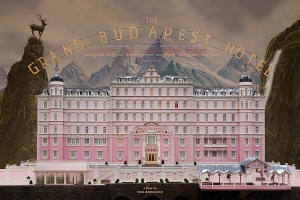

As many have others have noted, The Grand Budapest Hotel is in some ways the most intensely “Wes Andersonery film” (apparently this is becoming a common descriptor) that the director has yet made. From a purely aesthetic standpoint, this is hard to argue: the director’s signature visual ticks are so extreme here that they take on the point of near-parody. Anderson’s painstakingly intricate mise-en-scene, perfectly symmetrical shots, extreme contrasts in shallow and deep space composition, miniature model work, stop-motion effects, and overall celebration of artifice have all been taken to the nth degree in this film. Yet though he is playing with all of his favorite visual toys, this film is actually something of a diversion for the director. Anderson tends be as consistent thematically as he is visually, and few of his films are not on some level centered on selfish father figures, precocious genius children, and/or fraught sibling relationships. But while the director does not entirely avoid these themes in Grand Budapest Hotel, the film marks the first occasion where he doesn’t seem wholly consumed by them. Budapest is less about familial relationships being repaired, and more about the ways we turn to fantasy and storytelling once death places those relationships beyond repair. This is an idea that has always lurked somewhere beneath the surface of Anderson’s earlier films, but it seems to be the first time he’s addressed the idea head-on.

The result is also one of Anderson’s most tonally deceptive films, so much so that my initial reaction was one of mild disappointment. If one were to strip the film to its core narrative, it would easily be the most light-hearted and superficial film of the director’s career. Like a Pink Panther film where the animated opening credits never stop, the fanciful plot follows the adventures of Gustavo H, the concierge of the titular hotel during the 1930s in the fictional European Republic of Zubrowka. Early in the film, Gustavo is framed for murder, spurring a galloping story that constantly morphs from murder mystery to heist caper to prison escape thriller to globe-trotting adventure to farce, and likely circles back several times. At each step, the film seems to revel in the gleeful implausibility that come from these genre twists, casually resolving major story beats without explanation and bending the laws of physics in ways that would make Daffy Duck say, “um, this is a bit far-fetched, yes?” (I know, he’d probably have a more of a lisp, but it seems kind of rude to draw attention to it, doesn’t it? Are you really trying to make Daffy Duck self-conscious? Don’t you think he has it rough enough as it is?). At points, Anderson actually seems to be going out of his way to show that he can adapt his signature style to high concept genres, as in a surprisingly gruesome chase through a museum that plays like baby’s first Hitchcock thriller, or an alpine chase that plays like a James Bond film directed by Rankin and Bass. Indeed, this is easily the most cartoon-like film of the director’s career, and that includes his actual animated film, The Fantastic Mr. Fox. Throughout, Anderson keeps the momentum as breathless as a Road Runner short, buoyed by some of the funniest one- liners and absurdist gags of the filmmaker’s career.

Taken alone, all of this genre-hopping is not necessarily anything new for the director; certainly, key scenes from films like The Life Aquatic and Mr. Fox also gave us hints of what Wes Anderson’s version of an action or fantasy movie might look like. The key difference here lies in the hero at the center of the adventure. Earlier Anderson films never pretended that their characters were suited for these fantastic excursions – in the attack on the pirate island in Life Aquatic, for instance, much of the humor indeed comes from the stony faced Zissou and his band of introverted minions looking so ill-suited for this ‘80s action sequence. Conversely, Budapest has a hero who is just as wildly over the top and benign as the storybook world he inhabits. Gustave is a rare Anderson protagonist for many reasons, not the least of which being that he’s neither a precious child prodigy nor a selfish cad. The latter may seem like a strange claim, given that the character initially looks like a swindler and a scoundrel. Indeed, we learn early on that he regularly conducts romantic affairs with the wealthy elderly patrons of the hotel, and nearly every word out of his mouth is so floridly pompous and pretentious that he almost has to be full of shit. Yet as the film progresses, it gradually becomes clear that Gustave means every word of his hyper-articulate grandstanding. This is a man, we come to realize, who takes the genial bullshit the rest of us use as social lubrication with earnest sincerity. He’s a person for whom good customer service is not simply a professional policy, but a world-view that carries over into every aspect of his life. Even his proclivity towards sleeping with his elderly patrons registers less as the action of a sleazy hustler and more as a natural extension of his commitment to servicing his hotel guests. He’s by no means a flawless character; he’s prone to occasional cursing fits, and in one scene he lets out a shockingly nasty tirade of insults towards his loyal sidekick. But where earlier Anderson protagonists would hold on to this jerkish behavior until the very end of the film, Gustave immediately and sincerely apologies after each outburst; the film treats his lapses as humanizing quirks, rather than defining character flaws. As a result, Gustave does not receive any sort of character arc; he enters and exits the film as the same genial charmer.

In other words, this protagonist and the world he inhabits could never exist outside of the most whimsical of fantasy worlds. This is not a point the film expects us to overlook; indeed, Anderson regularly draws our attention to the fragility of this storybook universe. He does this primarily through multiple frame narratives, each of which situate the fantasy in bleaker contexts. The most important comes from Zero Moustafa, Gustave’s young sidekick in the main story who also narrates that story as world-weary old man. When the elderly Zero begins telling this story, most of its main characters have long since passed away, and the once-opulent hotel has fallen into a state of ruin. The narrator is clearly still in mourning for these friends and loved ones, and his sadness often plays at tonal odds with the jubilant story he’s ostensibly telling about them. Initially, we may expect these two narrative worlds to connect – for the frivolous business involving stolen paintings and prison escapes to evolve into a more serious tragedy that would explain the elderly Zero’s sad isolation. But this never actually happens – while we eventually learn about the unhappy circumstances that lead to Zero’s seclusion in the hotel, these tragic incidents have little to do with the manic yarn he tells about his youthful adventures with Gustave. Indeed, Agatha, the lover Zero seems the most devastated to have lost, scarcely features in this story. Though this may seem like sloppy writing on the part of the film’s director, that stark tonal disconnect between the light-hearted adventure and Zero’s later-day melancholy makes a poignant amount of sense. The events Zero narrates are not defining memories that would explain his present-day situation; rather, they’re pieces of a story he’s invented to distract himself from his grief.

That perspective throws the film’s fixation with exaggerated fantasy into sharp relief. What initially seems like Anderson indulging in his most precious and twee impulses instead emerges as a self-reflexive attempt to understand the appeal of precious and twee fantasies. All of the intensified stylistic devices – from the deep-space shots of his massive diorama sets to the shallow-space miniature shots that make mountains look like greeting card illustrations – all feed in to Zero’s attempt to craft a bubble of whimsy where real-world traumas can’t intrude. This is not the first time Anderson has explored this idea; as Mark Zollar Seitz notes in The Wes Anderson collection, characters like Max Fischer and Steve Zissou also seem to build ornate fantasy worlds as ways of coping with loss. But this is the first time Anderson has focused so squarely on the fantasy itself, rather than its creator. In Rushmore, we’re conditioned to observe Max Fischer’s elaborate theatrical productions with some level of detachment, our focus instead directed towards Max’s coming of age arc. Conversely, Budapest encourages us to get lost in the world Zero creates, so much so that it’s often easy to forget that this world is the product of its storyteller. Anderson pulls every stop to make that imaginary space seem infectiously appealing, and in the process he compels us to want to escape into this world nearly as much as Zero does.

Yet this escape can only be a temporary reprieve, as we remember every time the fantasy slams hard against the ugly realities that can’t be compressed into tidy genre conventions. Anderson emphasizes this point at regular intervals by cutting away from the bright candy-colored world of Gustave’s adventures to the stark and desolate hotel where the elderly Zero mourns. Some forces – war, human brutality, sickness, and death – are too cruel and capricious to fit into our attempts at turning our lives into stories, and Zero’s attempts at bending his memories into a storybook adventure can’t eradicate his saddest memories. As much as the film seems to celebrate fantasy, its final assessment is uncharacteristically bleak for the director. This is not a world where fantasy offers any sort of transformative healing power – nobody in the film ultimately matures or grows because of it. It provides minor solace for Zero’s sadness, but it does not prevent him from spending decades of his life holed up in a fading hotel, nursing his heartbreak in solitude.

But perhaps providing minor solace is enough. Zero’s narration is not the film’s only framing device, after all; he relays his story to a guest in the hotel, who decades later turns the story into a novel, which in turn a young girl reads at the author’s gravesite in the present day. These layers suggest that the fluffy diversion Zero has created for himself has a lasting power that extends past its author’s own grief. If it only serves as a brief relief for its maker, at least it can perform the same function for future generations of lonely dreamers. This is an ambivalent defense of fantasy at best, but it’s fitting that a film with such conflicted feelings about storytelling and escapism should end on a bittersweet question mark.

The Score:

The Grand Budapest Hotel marks Alexandre Desplat’s third collaboration with the Wes Anderson, and it’s arguably the most distinguished of the three. While Fantastic Mr. Fox and Moonrise Kingdom both had charmingly quirky scores that were perfectly suited for their films, I was never entirely clear on what Anderson thought he was getting from Desplat that he couldn’t have received from his former go-to composer, Mark Mothersbaugh (whose wonderful Baroque-jazz inspired music for films like Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums certainly did not lack for off-beat charm). In Grand Budapest, however, Desplat’s presence makes perfect sense, as the film’s setting gives the French composer room to stretch out into his distinctly European aesthetic. Romantic old-world European melodies along the lines of Maurice Jarre grace the hotel itself, while the film’s various chase scenes and montages inspire a charming mix of Eastern Europe and Nouvelle Vague-inspired jazz licks. As with Desplat’s other scores for the director, it’s extremely simple material, largely consisting of variations on a few brief themes (and indeed, long stretches seem to consist of various clever solo instruments taking turns jamming on the same seven chords). But while this means that the music can get a bit repetitive as a stand-alone listen, the score’s constant effervescence adds immeasurably to the film itself.

Indeed, Budapest is a unique Anderson film in that its soundtrack is almost exclusively score-driven. Where the director’s prior films are famous for their offbeat compilations of songs and classical pieces, Budapest’s soundtrack very rarely breaks away from Alexandre Desplat’s instrument underscore. And while I’m sure some may miss playing games of “Spot the Portuguese Bowie Cover/1950s Disney TV theme/Benjamin Britten oratorio” (and I’ll admit that I kind of do), it’s fitting that Budapest emphasizes music that does not call immediate attention to itself. Where those earlier song choices had the effect of temporarily pulling the audience out of the narrative, Desplat’s score subtly draws the listener into Budapest’s fantastic universe. Unsurprisingly, the score features most prominently in the scenes involving Gustave, where Desplat’s spritely European jazz is the perfect musical extension of the film’s feather-light artifice. The score sets a breathless pace that leaves little room for reflection, and its constant giddy tone keeps these scenes bouncing (my personal favorite cue is the cimbalom-driven, “The Society of the Crossed Keys,” a jangly piece that practically hops with glee).

The music is much sparser in the various framing sections. This is fitting, as it further accentuates the sharp contrast between the fantastic world of Gustave’s caper and the cold “real” worlds inhabited by Zero and his future listeners and readers. The exception is that Jarre-inspired romantic theme for the hotel, which occasionally whispers into scenes with the elderly Zero. In these moments, the wistful melody acts as a soft echo, a feint trace of a more innocent world that, to paraphrase Zero’s closing words, never actually existed. All told, it’s a deftly spotted score that knows precisely when to carry the film and when to let chilly silence make its impact.

Budapest is thus a recent high point for Desplat, and I’d say it was the same for Anderson if it wasn’t so hard to pick out the low points in his career. I don’t know that it’s productive to call this one of Anderson’s “best” films when just about all of them have been excellent, and most of the superlatives I’ve used to describe it (“delightful,” “charming,” “poignant,” “quirky,” “affecting”) could essentially apply to any Anderson film. But Budapest is charming and affecting in ways that are new for the director, and considering how many times Anderson’s films have often seemed like variations on the same themes, this is a significant development. After seven films that have kept us at an ironic remove from Anderson’s characters and their hand-made universes, The Grand Budapest Hotel finally drops these barriers and invites us inside one of those universes. And while the film populates that space with some of Anderson’s most exuberant and charming characters to date, the film is less interested in its characters than it is in its audience. For in the end, the film is most invested in our own relationship with fantasy and storytelling. It’s a film that gently but firmly interrogates our impulse to seek solace in fantasy worlds, even when those worlds are patently artificial, and even when we’re fully aware that they’re painfully impermanent.

Film: ****1/2/*****

Score: ****/*****

I feel like the movie has many similarities to the LIFE OF PI, which makes me see the movie as being about fiction itself – the weird framing device sets this up, as the story is mediated through so many different authors, and finally Anderson the director himself. But where that movie really deeply uses the “Story as trauma recovery” device, BUDAPEST just keeps it all brimming at the surface. Each story allows each author a new chance for self-invention, or at least the reinvent their conditions or their backdrop. The artificiality seems to derive from those continuing remediations (to use a term I always simplify because I don’t really like it). I don’t know anything about Zweig, but my guess is that his prose and characters mirrored Anderson’s manic, visual imagination….

Worthwhile thoughts, Paul. I found the film a bit sadder overall, but perhaps with a bit of historical awareness of what Zubrowka is standing in for, I was seeing where it was going before it went there. (Still, that didn’t rob the ending of its sobriety — the move from Gustave’s restoration to Zero’s second isolation in life is startlingly brief.)

I also concur with Andy about being reminded of Life of Pi in some ways — the strange fantasy of the story being told vs the framing device. I don’t think Pi’s framing device feels quite as suited to the film as this one does. And the wrapping up of the 3 framing devices in 30 seconds must be a record of narrative juggling.

Thanks, guys. I hadn’t considered the Life of Pi connection, but I see what you both mean. I think the key difference is that Life of Pi makes a pretty firm argument in favor of story as a trauma recovery device (with “story” in that instance extending to religion). There’s little question that Pi, the author, or the Japanese accountants are happier and better adjusted for choosing to believe in the fantasy. Budapest, on the other hand, seems much less willing to take a firm stand on whether or not storytelling has any significant power or value. Nobody gets to pretend that those Nazis are hyenas or tamable tigers at the end of this film.

[…] Who I Think Will Win: The Grand Budapest Hotel […]

[…] Who I Thought Would Win: The Grand Budapest Hotel […]

[…] https://moviemusicmusings.wordpress.com/2014/04/15/grand-budapest-hotel-film-and-score-review/ […]